|

Cybertelecom Federal Internet Law & Policy An Educational Project |

Special Access

|

Special Access |

|

|

|

Special Access Data Collection Overview

"Special access lines are dedicated high-capacity connections used by businesses and institutions to transmit their voice and data traffic. For example, wireless providers use special access lines to funnel voice and data from cell towers to wired telephone and broadband networks. Small businesses, governmental branches, hospitals and medical offices, and even schools and libraries use special access for the first leg of communications with the home office. Branch banks and gas stations even use special access for ATMs and credit card readers. The FCC has the obligation to ensure that special access lines are provided at reasonable rates and on reasonable terms and conditions."

Derived From: Government Accountability Office, FCC Needs to Improve its Ability to Monitor and Determine the Extent of Competition in Dedicated Access Services, Report 07-80 (Nov. 2006).

Government agencies and businesses rely on “special access” services (also known as “dedicated access”) to meet their voice and data telecommunications needs (i.e., large volumes of long-distance services, secure point-to-point data transmissions, and reliable Internet access).1 The federal government, with its extensive network of agency offices spread throughout the nation, is a major consumer of these services. Due to increasing data transmission needs, these dedicated access services are a growing segment of the telecommunications market and represented about $16 billion in revenues in 2005 for the major providers of those services—the largest incumbent telecommunications firms (i.e., AT&T Corporation [formerly SBC Communications], BellSouth Corporation, Qwest Communications, and Verizon Communications). The incumbent firms have an essentially ubiquitous local network that generally reaches all of the business locations in their local areas. For long-distance or other telecommunications companies (such as Sprint Nextel, Time Warner Telecom, and Level 3 Communications) to provide their services to large business customers, they often purchase dedicated access services on a wholesale basis from the incumbents for local connectivity. The incumbent firms have stated that the majority of the dedicated access services they sell are sold wholesale to other carriers. Alternatively, competitors may build out to reach customers using their own facilities, or purchase connections from other competitive carriers that have built out to those businesses, resulting in “facilities-based” competition. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 (the 1996 Act), allowed the major incumbent firms to compete in the long-distance market;2 therefore, incumbent firms are now competing to provide businesses with long- distance services as well as acting as a wholesale supplier of local connectivity to their competitors.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which is an independent United States government agency, regulates interstate and international communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable. Because the major incumbent firms initially controlled all dedicated access connections, prices for these services have traditionally been regulated by FCC. In 1991, FCC implemented a system of regulations that altered the manner in which the incumbent firms established interstate dedicated access prices. FCC “capped” the prices that could be charged by the large incumbent firms. (Those firms are hereafter called “price-cap incumbents.”)3 The 1996 Act, which Congress designed to foster a procompetitive, deregulatory national policy framework for the United States telecommunications industry, led FCC to reconsider its current regulatory framework for access prices, including whether and how to remove price-cap incumbents’ access services from price caps and tariff regulation once they are subject to substantial competition.

In 1999, FCC issued the Pricing Flexibility Order,4 which, among other things, permitted the deregulation of prices for dedicated access services in metropolitan statistical areas (MSA)5 where price-cap incumbents could show that certain “competitive triggers” had been met. The competitive trigger refers to the extent to which competitors have “colocated” equipment in a price-cap incumbent’s wire center (i.e., an aggregation point on a local telecommunications’ network).6 FCC determined that once a certain level of colocation in wire centers throughout a metropolitan area had been achieved, it was a good predictor that competitors had made significant, irreversible sunk investments in facilities, and indicated the likelihood that a competitor could eventually extend its own network to reach its customers. In FCC’s view, sufficient sunk investments of this sort would constrain monopoly behavior by price-cap incumbents. Accordingly, FCC determined that colocation at the wire center level can reasonably serve as a measure of competition in a given MSA, rather then looking to more granular assessments of the level of competition at a building level or at the level of individual customers. FCC also determined that the colocation-based triggers would not be overly burdensome on parties and on FCC’s limited resources as would be more granular assessments. The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia affirmed FCC’s decision to grant additional pricing flexibility to price-cap incumbents through a series of colocation-based triggers.7

Depending on the extent of competitive colocation that is achieved in an MSA, FCC grants either partial or full pricing flexibility to the price-cap incumbent carriers.8

In MSAs where price-cap incumbents can demonstrate a certain level of competitive colocation, they would satisfy the triggers that would result in partial price deregulation (known as “phase I” flexibility). With phase I flexibility, FCC allows price-cap incumbents to offer customized contracts to customers that provide discounts off the price-capped “list prices.” This flexibility was designed to allow price-cap incumbents to more adequately respond to competition, where price-cap regulation may be too constricting to allow the incumbent to lower its prices to respond to competitive pressures. Price-cap incumbents must file their contract terms and conditions—-on a day’s notice—with FCC and make that same contract available to other customers that meet the contract’s specified terms and conditions. Alternatively, for customers that do not sign up for contracts, incumbents are required to offer dedicated access at price- capped prices. Those prices may include term and volume discounts (e.g., lower list prices may exist for 3-year or 5-year terms compared with month-to-month list prices or for purchasing greater amounts of dedicated access).

In MSAs where price-cap incumbents can demonstrate a higher level of competitive colocation, price-cap incumbents may meet more stringent competitive triggers and qualify for greater price deregulation (known as “phase II” flexibility). Because FCC deems phase II areas to be sufficiently competitive to ensure that rates for dedicated access are just and reasonable, phase II flexibility frees the incumbent from price caps and allows it to raise or lower its list prices. Price-cap incumbents must still file these new “price-flex” list prices with FCC. As with phase I flexibility, contracts can be offered that provide additional discounts to respond to competitive pressures.

Where neither trigger for competition is met, price-cap incumbents’ prices remain subject to FCC’s price cap and customers can only purchase dedicated access from the price-capped list prices (which can include volume and term discounts).

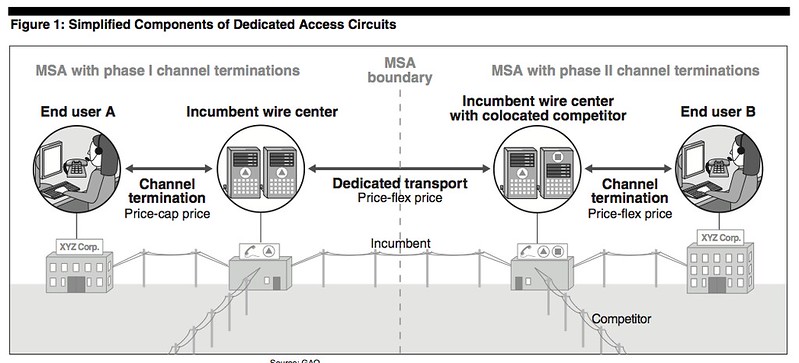

FCC’s pricing flexibility pertains to two separate components of dedicated access services—the end user channel termination and dedicated transport. In general, the end user channel termination component (sometimes referred to as a “local loop”) connects an end user’s location (e.g., the corporate headquarters or field office) with the nearest incumbent’s serving wire center. The dedicated transport component connects one wire center to another wire center or to another carrier’s point of presence. Figure 1 illustrates these components in MSAs with different levels of pricing flexibility for channel terminations and the pricing that applies for each component. In the MSA on the left-hand side of the figure, the price-cap incumbent has received phase I flexibility for channel terminations. As figure 1 shows, with phase I flexibility, the price- cap price is still available for channel terminations. In the MSA on the right-hand side of the figure, the incumbent has received phase II flexibility for channel terminations, and the price-flex price is used. If a competitor is colocated in the wire center as the figure illustrates, FCC has noted that the potential exists for the competitor to build out its own network to end user B.

In 2000, prior to its granting any pricing flexibility, FCC further reformed its price-cap rules. That reform was initiated by a group of incumbent firms and long-distance companies, called the Coalition for Affordable Local and Long Distance Service (CALLS).9 The CALLS plan was envisioned as a 5-year transitional regime to resolve, among other things, price-cap issues.10 Specifically, as FCC adopted, the CALLS plan provided for yearly reductions in price caps for dedicated access services based on agreed-upon percentages. The percentage decreases were 3 percent in 2000 and 6.5 percent each year from 2001 through 2003. Beginning in 2004, price-cap rates have essentially been frozen, with no further decreases in prices, with the exception of adjustments based on cost factors outside of the incumbents’ control (e.g., taxes and fees). The “CALLS Order” was intended to run until June 30, 2005, but the order remains in place until FCC adopts a subsequent plan.

In 2001, concurrently with the scheduled decreases in price caps resulting from the CALLS Order, FCC began granting pricing flexibility to price-cap incumbents. Some level of pricing flexibility has since been granted to the four major price-cap incumbents in 215 of the 369 MSAs in the United States and Puerto Rico. These four price-cap incumbents have received full price deregulation (phase II for all circuit components) in 112 MSAs. Only 3 of the 100 largest MSAs in the United States and Puerto Rico are not under any pricing flexibility.11

In January 2005, in response to a petition that AT&T filed in 2002, FCC initiated a rulemaking proceeding on dedicated access price regulation to examine whether the pricing flexibility rules should remain intact or be revised.12 The basic economic theory underlying FCC’s regulatory approach postulates that greater competition should constrain incumbent pricing power and drive prices toward the marginal cost of providing those dedicated access services. However, competitors and business customers have raised concerns that, in places where FCC has granted phase II pricing flexibility, prices have incongruously risen. Concerns also have been raised that the competitive triggers that FCC used were inadequate to accurately judge the extent of competition in the market. Price-cap incumbents, on the other hand, generally oppose the petition. They contend that their dedicated access rates are reasonable, that there is robust competition in the dedicated access market, and that the colocation-based triggers are an accurate metric for competition. FCC’s rulemaking is still ongoing.

Recent mergers of major telecommunications firms—SBC’s acquisition of AT&T (and subsequently assuming the AT&T name); Verizon’s merger with MCI; and, more recently, AT&T’s proposed purchase of BellSouth— have further complicated the issues surrounding dedicated access services. As long-distance companies, the former AT&T and MCI were two of the largest purchasers of dedicated access services from the incumbents and were major competitors for providing large business customers with telecommunications services. At the federal level, FCC and the Department of Justice (DOJ) reviewed these mergers.13 DOJ filed separate civil antitrust complaints on October 27, 2005, seeking to enjoin the proposed acquisitions. DOJ found the likely effect of these acquisitions would be to lessen competition substantially for dedicated access in 19 metropolitan areas.14 FCC approved the proposed mergers on October 31, 2005, subject to the parties’ agreeing to certain commitments, including freezing the prices for dedicated access for 30 months.15 More recently, AT&T announced plans to purchase BellSouth. Concerns have been raised that this proposed merger also may lessen competition in the dedicated access market. FCC’s review of this merger is ongoing.

The availability of unbundled network elements (UNE) also complicates the issues surrounding facilities-based competition in dedicated access because they are functional equivalents to certain dedicated access services, but, where available, are generally less expensive than dedicated access services.16 The 1996 Act gave the FCC broad power to require incumbent firms to make UNEs available to competitive carriers to provide them with local connectivity.17 Recently, a federal appellate court upheld FCC’s fourth attempt to impose UNE rules.18 Under the new rules, FCC modified its unbundling framework19 for high-capacity loops and transport. The Commission adopted a wire-center-based analysis that used the number of access lines and fiber colocations in a wire center as proxies to determine impairment for high-capacity loops and dedicated transport.20 Where such triggers are not met, the incumbent must make UNEs available at rates based on forward-looking economic costs.21 FCC hopes that this framework will lead to the right incentives for both incumbents and competitors to invest rationally in the telecommunications market.

Broadband Plan Recommendations

- Recommendation 4.8: The FCC should ensure that special access rates, terms and conditions are just and reasonable.

"Special access circuits are usually sold by incumbent local exchange carriers (LECs) and are used by businesses and competitive providers to connect customer locations and networks with dedicated, high-capacity links.79 Special access circuits play a significant role in the availability and pricing of broadband service. For example, a competitive provider with its own fiber optic network in a city will frequently purchase special access connections from the incumbent provider in order to serve customer locations that are “off net.” For many broadband providers, including small incumbent LECs, cable companies and wireless broadband providers, the cost of purchasing these high-capacity circuits is a significant expense of offering broadband service, particularly in small, rural communities.

The FCC regulates the rates, terms and conditions of these services primarily through interstate tariffs filed by incumbent LECs. However, the adequacy of the existing regulatory regime in ensuring that rates, terms and conditions for these services be just and reasonable has been subject to much debate.

Much of this criticism has centered on the FCC’s decisions to deregulate aspects of these services. In 1999, the FCC began to grant pricing flexibility for special access services in certain metropolitan areas. Since 2006, the FCC has deregulated many of the packet-switched, high-capacity Fast Ethernet and Gigabit Ethernet transport services offered by several incumbent LECs. Business customers, community institutions and network providers regard these technologies as the most ef- ficient method for connecting end-user locations and broadband networks to the Internet.

The FCC is currently considering the appropriate analytical framework for its review of these offerings. The FCC needs to establish an analytical approach that will resolve these debates comprehensively and ensure that rates, terms and conditions for these services are just and reasonable.

Proceedings

- BUSINESS DATA SERVICES IN AN INTERNET PROTOCOL ENVIRONMENT; TECHNOLOGY TRANSITIONS; SPECIAL ACCESS FOR PRICE CAP LOCAL EXCHANGE CARRIERS; AT&T CORPORATION PETITION FOR RULEMAKING TO REFORM REGULATION OF ILEC RATES FOR INTERSTATE SPECIAL ACCESS SERVICES. Consistent with precedent, WCB grants, dismisses, or denies a number of requests for review, requests for waiver, and petitions for reconsideration of decisions related to actions taken by the Universal Service Administrative Company. (Dkt No. RM-10593 13-5 05-25 16-143 ). Action by: the Commission. Adopted: 04/20/2017 by R&O. (FCC No. 17-43). WCB https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-17-43A1.pdf

https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-17-43A2.docx

https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-17-43A3.docx

https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-17-43A4.docx

https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-17-43A2.pdf

https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-17-43A3.pdf

https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-17-43A4.pdf- Business Data Services in an Internet Protocol Environment, WC Docket Nos. 16-143, 15-247, 05-25, RM 10593, Tariff Investigation Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 21 FCC Rcd 4723, 4818 ¶ 216 (2016) (“concentration by any measure is high” in the BDS market)

"In 2007, the Bureau sought to update the record in the special access proceeding. In 2005, the Commission had released the Special Access NPRM,[1] noting that an examination of the state of competition in the marketplace is critical to a determination of whether the Commission’s pricing flexibility rules have worked as intended. The Bureau sought to refresh the record in that proceeding in light of a number of developments, including: 1) a number of significant mergers and other industry consolidations;[2] 2) the continued expansion of intermodal competition in the market for telecommunications services, 3) the release by GAO of a report summarizing its review of certain aspects of the market for special access services;[3] and 4) rapid changes in fiber technologies.[4]

"In 2009, the Bureau asked parties to comment on an appropriate analytical framework for examining the various issues that have been raised in the Special Access NPRM.[5] The Bureau explained that “the Commission would benefit from a clear explanation by the parties of how it should use data to determine systematically whether the current price cap and pricing flexibility rates are working properly to ensure just and reasonable rates, terms, and conditions and to provide flexibility in the presence of competition.”[6] This proceeding will help ensure that the rates, terms and conditions for special access services available to small businesses and entrepreneurs are just and reasonable.[7]

- CONNECT AMERICA FUND; ETC ANNUAL REPORTS AND CERTIFICATIONS; DEVELOPING A UNIFIED INTERCARRIER COMPENSATION REGIME; ACCESS CHARGE TARIFF FILINGS INTRODUCING BROADBAND-ONLY LOOP SERVICE. Waived Sections 69.311 and 69.416 to limit the costs that must be shifted from the Special Access category to the Consumer Broadband-only Loop category in certain specific circumstances. (Dkt No. 01-92 14-58 16-317 10-90 ). Action by: Chief, Wireline Competition Bureau. Adopted: 12/14/2016 by ORDER. (DA No. 16-1383). WCB https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/DA-16-1383A1.docx

https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/DA-16-1383A1.pdf- FCC NPRM :: Developing a New Regulatory Framework for Business Data Services (Special Access) (6/3/2016) "In this document, the Federal Communications Commission seeks comment on replacing the existing, fragmented regulatory regime applicable to business data services (BDS) (i.e., special access services) with a new technology-neutral framework, the Competitive Market Test, which subjects non-competitive markets to tailored regulation, and competitive markets to minimal oversight.Comments are due on or before June 28, 2016; reply comments are due on or before July 26, 2016. "

- Business Data Services in an Internet Protocol Environment, et al, Tariff Investigation Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 31 FCC Rcd 4723 (2016)

- Released: 02/17/2016. ADDITIONAL PARTIES SEEKING ACCESS TO DATA AND INFORMATION FILED IN RESPONSE TO THE BUSINESS DATA SERVICES (SPECIAL ACCESS) DATA COLLECTION. (DA No. 16-161). (Dkt No RM-10593 05-25 ) Objections Due by: February 24, 2016. WCB

- Released: 06/24/2015. WIRELINE COMPETITION BUREAU FURTHER EXTENDS COMMENT DEADLINES IN SPECIAL ACCESS PROCEEDING. (DA No. 15-737). (Dkt No RM-10593 05-25 ). Comments Due: 09/25/2015. Reply Comments Due: 10/16/2015. WCB .

- FCC TAKES MAJOR STEP IN REVIEW OF COMPETITION IN $40 BILLION SPECIAL ACCESS MARKET. News Release. News Media WCB

Released: 09/17/2015.

- PARTIES SEEKING ACCESS TO DATA AND INFORMATION FILED IN RESPONSE TO THE SPECIAL ACCESS DATA COLLECTION. (DA No. 15-1038). (Dkt No RM-10593 05-25 ) Objections Due: 09/24/2015. WCB .

- Data Requested in Special Access NPRM, Public Notice, 25 FCC Rcd 15146 (WCB 2010).

- Wireline Competition Bureau Announces July 19, 2010 Staff Workshop to Discuss the Analytical Framework for Assessing the Effectiveness of the Existing Special Access Rules, Public Notice, 25 FCC Rcd 8458 (WCB 2010).

- Parties Asked to Comment on Analytical Framework Necessary to Resolve Issues in the Special Access NPRM, WC Docket No. 05-25, DA 09-2388 (rel. Nov. 5, 2009)

- Parties Asked to Refresh Record in the Special Access Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, WC Docket No. 05-25, Public Notice, 22 FCC Rcd 13352 (2007)

- Special Access Rates for Price Cap Local Exchange Carriers, WC Docket No. 05-25, AT&T Corp. Petition for Rulemaking to Reform Regulation of Incumbent Local Exchange Carrier Rates for Interstate Special Access Services, RM-10593, Order and Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 20 FCC Rcd 1994 (2005) (Special Access NPRM)

Reports

- Federal Communications Commission: Special Access for Price Cap Local Exchange Carriers; AT&T Corporation Petition for Rulemaking To Reform Regulation of Incumbent Local Exchange Carrier Rates for Interstate Special Access Services GAO-13-340R: Feb 6, 2013

- Government Accountability Office, FCC Needs to Improve its Ability to Monitor and Determine the Extent of Competition in Dedicated Access Services, Report 07-80 (Nov. 2006).

- "In the 16 major metropolitan areas we examined, available data suggest that facilities-based competitive alternatives for dedicated access are not widely available. Data on the presence of competitors in commercial buildings suggest that competitors are serving, on average, less than 6 percent of the buildings with demand for dedicated access in these areas. For buildings with higher levels of demand, facilities-based competition is more moderate, with 15 to 25 percent of buildings showing competitive alternatives, depending on the level of demand. Limited competitive build out in these MSAs could be caused by a variety of entry barriers, including government zoning restrictions and difficulty gaining access to buildings from building owners. In addition, where demand for dedicated access is relatively small, it is unlikely to be economically viable for competitors to extend their networks to the end user. FCC has also noted that, where competitors can lease unbundled network elements from incumbent providers, there may be less incentive for competitors to invest in their own facilities.

- Available data suggest that incumbents’ list prices and average revenues for dedicated access services have decreased since 2001, resulting from price decreases due to regulation and contract discounts. However, in areas where FCC granted full pricing flexibility due to the presumed presence of competitive alternatives, list prices and average revenues tend to be higher than or the same as list prices and average revenues in areas still under some FCC price regulation. According to the large incumbent firms, many large customers needing service in areas with pricing flexibility purchase dedicated access services under contracts that provide additional discounts. However, GAO found that contracts do not generally affect the differential cited previously, and that contracts also contain various conditions or termination penalties competitors argue inhibit customer choice. Government agencies, to the extent that they purchase dedicated access off of General Services Administration contracts, are generally shielded from price increases due to prenegotiated rates. However, not all agencies purchase off of these contracts.

- FCC uses various data to assess competition in dedicated access, but these data are limited in their ability to describe the state of competition accurately. For example, these data measure potential competition at one point in time and are not revisited or updated, even though competitors may enter bankruptcy or be bought by the incumbent firm. FCC also collects data from external parties through its rulemaking proceedings, but those parties have no obligation to provide data, and FCC has limited mechanisms to verify the reliability of any data submitted. FCC’s strategic plan and various rulemakings have defined FCC’s obligation to assess and ensure competition in dedicated access. FCC stated that gathering and analyzing additional data would be costly and burdensome. Yet without more complete and reliable data, FCC is unable to determine whether its deregulatory policies are achieving their goals.

Merger Conditions

- AT&T / Bell South 2007: Special Access

Govt Activity

- “Remarks of FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler CTIA Super Mobility Show 2016, Las Vegas,” (Sept 7, 2016) (reasonable pricing and availability of business data services are essential to the deployment of 5G wireless networks)

- Chairman Tom Wheeler, Testimony before the Subcommittee on Communications and Technology, Committee on Energy and Commerce, U.S. House of Representatives, at 69 (Nov. 17, 2015), (stating, “you can’t have cell densification, whith makes wireless networks work better, without backhaul, which requires special access”);

- Chairman Tom Wheeler, Federal Communications Commission, Remarks at INCOMPAS Policy Summit, at 1-2 (Apr. 11, 2016) (stating, “[w]ithout a healthy BDS market, we put at risk the enormous opportunity for economic growth, job creation and U.S. competitiveness that 5G represents”)

- Letter from Julius Genachowski, Chairman, FCC, to Henry A. Waxman, Chairman, Committee on Energy and Commerce, U.S. House of Representatives, attach. at 4 (July 1, 2010), (“Special access services is a common carrier telecommunications service subject to statutory requirements under Title II of the Communications Act.”)

Papers

© Cybertelecom :: © Cybertelecom ::