|

Cybertelecom Federal Internet Law & Policy An Educational Project |

|

Layers and the FCC's Approach to the Internet |  |

|

|

Communications carriers provide a platform over which information is exchanged. Business negotiations, social engagements, political discourse, religious gatherings, scientific research, education, medical care, and more - all can transpire over a communications carrier. The better and more open the platform, the more the dialog can flourish. [See ACLU v. Reno 1997 ("[T]he Internet may fairly be regarded as a never-ending worldwide conversation.")]

The line between carrier and information carried has historically been bright. With traditional carriers optimized for specific applications - the line between content and network has been a distinct boundary. The postal service transmits content in the form of letters. The telegraph network transmitted content in the form of telegrams. The telephone network transmits content in the form of audible communications.

With postal, telegraphy and telephony services, there was generally one monopoly provider of each network service, over which end users could interact with any person, any content, anywhere.

Reinventing the Telephone Network

Things became murky starting in the 1960s. Computers were introduced to the network. Some computers helped operate the telecommunications network; some computers were interacted with over the telecommunications network; and some computers did both, operating the network at peak capacity and offering data processing services during off peak hours. Recognizing the innovative and economic promise of computer networks, the FCC launched the Computer Inquiries in order to ensure that computer networks could acquire the telecommunication services they needed to grow.

Computer scientists engaged in taking a telephone network optimized for voice and retrofitting it for communications between computers. The telephone network wasn't designed for computer communications - but they would innovate until they had a new network, a computer network utility, that provided communications for computers much like AT&T had provided communications for humans.

The first attempt of the FCC to distinguish between this computer and that computer was a muff. Focusing on the technology, the FCC attempted to divine which computers were data processing services and which were communications. This paradigm failed to establish a bright line. There was a big gray area in the middle that led to a plethora of case-by-case analysis and the eventual collapse of the Computer I model.

In the mean time, Paul Baran, who wrote the RAND paper on packet switching, lectured at the FCC; Larry Roberts, who was head of ARPANet, left ARPA, consulted with FCC staff, and then set up the first commercial packet-switched network Telenet,; and Steve J. Lukasik, Director of ARPA, became the FCC's Chief Technologist. ARPANet's paradigm for computer networks became infused into FCC policy considerations. The Internet was, by design, a computer network, connecting otherwise incompatible physical networks, in order to support the research and innovation occurring at the ends (i.e., the end-to-end design). As shown by the Internet Hourglass, the Internet design was that of a Lego set. The Internet could be provisioned over any physical network: fiber, wireless, satellite, copper, optical. The Internet could support any application: email, world wide web, games. One layer did not interface with another. For example, email applications did not interface with the physical Ethernet layer. Each layer's services were offered by a different provider (telephone company, ISP, application service provider, content provider), with different equipment (switches, routers, servers), from different vendors. The strength of the Internet is that the Internet itself is a very simple middle network protocol that enables the end user to use it over any network and support any enhancements from any source.

Computer II :: FCC Adopts the Layered Model

In Computer II, the FCC adopted the basic service versus enhanced service dichotomy. This vision of how computer networks are built on top of telecommunications networks focused on the service provided to the end user and not the technology, and tracks the Internet layered model. The bottom physical network layer is the basic telecommunications service, provided by a carrier with market power who has both incentive and ability to discriminate. Imposed on this carrier are regulatory safeguards in order to ensure an open communications platform upon which innovators can build computer networks. The enhanced services are "unregulated" but are the primary beneficiary of the Computer Inquiry policy.

The FCC's purpose was to identify what is the basic telecommunications service that is subject to regulatory obligations and what is not. While there are many layers to the layered model, the FCC was only concerned with identifying one boundary: the line between the physical network and any enhancement above that network. Having identified a network carrier upon which innovation can take place, the open communications platform has been established and anything more is an enhancement. You would never identify a common carrier over a common carrier; that would be a pointless redundancy that adds nothing. Once an open network platform has been established, identifying another open network platform doesn't make the platform any more open. The FCC also had no need to distinguish between the computer network, applications, or content; they were all enhancements. The Computer II enhanced services versus basic services model would flourish for two decades.

During the Computer Inquiries, there was generally one monopoly provider of network service, over which end users could interact with any computer network, any application, any person, any content, any where. When the commercial ISP market was unleashed, end users generally had one ISP, but they could have more, and they could switch ISPs with ease.

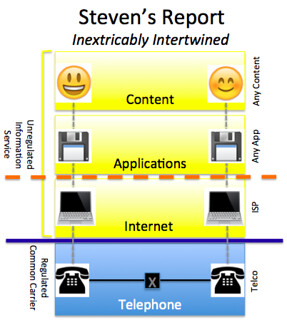

Steven's Report :: Inextricably Intertwined

By 1998, the commercial Internet had been unleashed and the Telecommunications Act had been passed. Sen. Stevens from Alaska asked the FCC if the Internet was not in fact harming the Universal Service Fund that ensures affordable telecommunications service in rural and high cost markets. The Steven's Report was one of the FCC's first articulations of Internet policy. Responsive to the Senator's concerns, the FCC noted that Internet networks, at that time, were built acquiring telecommunications services from telephone companies. The more people used the Internet, the more Internet providers and end users consumed telecommunications services, and the more money is contributed to the universal service fund.

An ISP provides "Internet access." That is the one service that the end user must acquire from the ISP. Having acquired Internet access from an ISP, the end user then can install the applications of choice (email, world wide web, USENET) to access content of choice. Here the FCC is articulating the classic Internet layered model where the end user (and the ISP) is acquiring telecommunications service from the telephone company, acquiring Internet access from the ISP, and utilizing any application from any source to interact with any information from any source. [Steven's Report paras. 73-82].

The FCC then said something surprising…. and unnecessary.

the provision of Internet access service crucially involves information-processing elements as well; it offers end users information-service capabilities inextricably intertwined with data transport.

Steven's Report at 80 (emphasis added). The FCC was rebuffing calls from Senators to classify Internet-over-dial-up as a telecommunications service, as well as Sen. Stevens and Burns arguments that email itself should be classified as a telecom service, "just like a fax" (note that faxes themselves are not a telecom service; the telephone line over which a fax is used is a telecom service) [Steven's Report para. 78]. The Commission wanted to stand on precedent that the Internet is an information service, and reject any cherry picking that might attempt to pick off something like email that could be construed as a transmission to a destination of the end users choosing without change in form or content. The FCC stated

More generally, though, it would be incorrect to conclude that Internet access providers offer subscribers separate services -- electronic mail, Web browsing, and others -- that should be deemed to have separate legal status, so that, for example, we might deem electronic mail to be a "telecommunications service," and Web hosting to be an "information service." The service that Internet access providers offer to members of the public is Internet access.

Steven's Report para. 79. Wanting to reject any notion that one could bust the Internet into parts and then decide which parts were telecommunications service and which were information services, the FCC made that fateful statement

the provision of Internet access service crucially involves information-processing elements as well; it offers end users information-service capabilities inextricably intertwined with data transport.

Steven's Report at 80 (emphasis added). "The Internet is a bundle that cannot be dissected," the FCC attempted to argue.

It wasn't true. And it wasn't necessary. The FCC had already argued that Internet access over dial-up, email, the World Wide Web, and other applications, were information services. Again, Computer Inquiry policy is to identify the physical network with market power, classify that as basic telecommunications service, and impose safeguards to ensure an open platform upon which one can build cool stuff. Having identified the basic telecommunication service, anything more is an enhancement. It is a bright line test. The FCC's conclusions were consistent with precedent. But the FCC was anxious about fending off attempts to regulate the Internet, and thus attempted to defend against the threat of dissection.

Whatever it was that the "inextricably intertwined" dicta meant, it did not mean that the Internet layered model had altered:

- The end-user and the ISP still purchased telecommunications service from a telephone company, using equipment from a telecommunications vendor (i.e., a Nortel SS7 switch). The end-user could use that telephone line to call anyone, connect to any ISP, place a fax, and anything else.

- An end-user could subscribe to one of multiple ISPs in a market. With standardized dial-up modems over telephone lines, switching ISPs was relatively easy. If an ISP provided inferior service, the end-user could simply switch providers.

- The Internet service is offered by Internet service providers using routers and services from Internet vendors (i.e., CISCO, SUN).

- Once connected to the ISP, the consumer could use any DNS service. The late 1990s, the Internet community was still embroiled in the Internet governance wars. Alternative DNS roots were set up and were used, although generally consumers simply used the DNS service of their ISP.

- Once connected to the ISP, the consumer could use any application, interact with any content, and communicate with any person anywhere. ISPs generally provided software with the account, but alternative software, such as the Netscape browser, frequently proved preferable. Hotmail, a web-based email service, provided end users email service that was not tied to their ISP, allowing end users to access the email from anywhere and take the email service with them if they switched ISP service.

- There was no interface directly between the telecommunications service and the Internet service.

Whatever "inextricably intertwined" meant, the Internet remained a collection of Lego blocks that could be snapped together and taken back apart at the choice of the end user.

During the late 1990s, there was some competition among telephone providers as CLECs attempted to enter the market. End users generally subscribed to one ISP but could easily switch ISPs. With Internet access, end users could interact with any computer network, any application, any person, any content, anywhere.

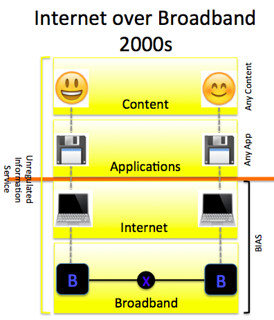

Internet over Broadband :: Single, Integrated Service

The language from the Steven's Report was picked up by the Internet over Broadband proceedings in the 2000s, sort of. In the 2002 Internet over Cable Proceeding (a.k.a. BrandX), the FCC stated

In the [Steven's] Report, the Commission found that Internet access service is appropriately classified as an information service, because the provider offers a single, integrated service, Internet access, to the subscriber.

[Internet over Cable para. 36 (emphasis added)] The Internet over Cable proceeding swapped "inextricably intertwined" with "single, integrated Internet service" and proceeded.

There was one significant difference. Now the provider of the physical network and the Internet service was one BIAS provider. The end user no longer acquired telephone service from the telco and Internet service from an ISP. Now the end user acquired from the BIAS provider the physical network service and Internet access services, as well as, blundled with it, cable TV and telephony services.

The question before the FCC was whether this should be the broadband world we were entering, or whether the BIAS provider should unbundle network telecommunications service from Internet service, thereby allowing the end user to access an ISP of choice (a.k.a. Open Access). The answer of the FCC was a policy decision that those investing in broadband should be able to retain maximum revenue and not be forced to unbundle their network investment to competitors - thereby increasing incentives to invest in broadband. The FCC did not want to put providers in a position of investing in networks only to have to unbundle them for competitors. Therefore the FCC adopted the "inextricably intertwined" / "single, integrated service" language of the Steven's Report, concluded that there was no severable telecommunications service that could be unbundled. The goal was a market with competition between different physical networks, with investment in DSL, fiber, cable, optical, powerline, and wireless networks, that would compete, discipline network providers, and serve end users.

The competitive broadband Internet access market did not materialize. The result was a non-competitive Internet over broadband market, that tilted towards cablecos, where end users faced high switching costs, where the provider would have both incentive and ability to discriminate, and where there would be no common carriage policy protecting against discrimination. Discriminatory behavior occurred, and calls for network neutrality emerged.

The Internet had not changed. The Internet still followed the layered model. The Internet still connected incompatible physical networks (DSL, fiber, cable, optical, wireless). The physical network underneath could have been unbundled and sold to the consumer as a network service; the BIAS providers simply elected not to do that. Instead, the end user had a choice of one physical network provider in a market that was simultaneously the one choice of Internet service and was bundled with cableTV and telephone service. Switching bundled network services was difficult, involved truck rolls and installation of different proprietary equipment, and generally did not occur if it could occur.

During the 2000s, BIAS providers emerged to dominate the Internet access market. End users generally subscribed to one provider which bundled broadband Internet, cableTV, and TV service. There was no choice of alternative Internet access service; there was no ability to acquire underlying telecom service. Above the Internet layer, the end user continued to be able to interact with any DNS service, any application, any content, and any person anywhere.

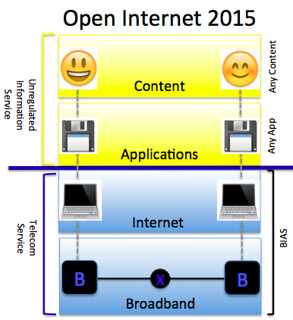

Open Internet 2015

The experiment of the elimination of common carriage collided with discriminatory behavior of the network providers. Consistent with one hundred plus years of jurisprudence, network providers have the incentive and the ability to discriminate, did so, and that's a problem.

But if the network provider did not want to unbundle the physical network layer and sell it to end users, where should the line be drawn that delineates the telecommunications service? The answer of the Open Internet 2015 Order is that the Internet network layer provided a communications network service where information is transmitted to end-points of the end users choice, without change in form or content. The change in form and content takes place at the ends, with the applications interacting with content.

If Internet access could now be classified as a telecommunications service, why had it not been classified as a telecommunications service before? Because before the basic telecommunications service in the form of the telephone network had already been identified. Anything build on top of the communications carrier platform was an enhancement. Taking the telephone network service and turning it into a different network was an enhancement. Having identified the telecommunications platform, common carriage goals of stopping discrimination and supporting communications had been achieved; identifying a carrier over a carrier did not add any additional protection. So in the dial-up world, Internet access would not be a telecommunications service because dial-up telephone service already was.

Now, Internet access service was the first physical network service sold to the end user that provided the end user the ability to communication with anyone anywhere. Below Internet access service there was no other common carrier communications platform. Thus, identifying this as the communications platform upon which people could communication and do cool things was reasonable.

Continuing the BIAS provider model, end users generally subscribed to one provider which bundled broadband Internet, cableTV, and TV service. There was no choice of alternative Internet access service; there was no ability to acquire underlying telecom service. Above the Internet layer, the end user continued to be able to interact with any DNS service, any application, any content, and any person, anywhere.